I recently gave a talk at UXBrighton about running user tests for virtual reality. The event was a really fun evening, with some great talks from Deborah Amar and Henry Ryder, and was organised by Harvey from Player Research.

In my talk, I covered some tips that I’d learned from running user research for virtual reality hardware, and many virtual reality experiences. I’ve copied the slides and my notes below for your viewing pleasure. Enjoy!

Ok, so here we go….

For the last few years, I’ve been working a lot on VR, including running research on the hardware itself, the system software and the launch games for the PlayStation VR headset…

…but who cares about that. Today I’ll be sharing some things I’ve learned during running these sessions, in particular for 1:1 moderated lab-based sessions. Some of the points we come across may seem obvious in hindsight, but hopefully they will save you wasting a participant, a research session, or worse by encountering easy to overcome issues.

The first area I wanted to talk about was how to set up the room for VR, which needs some extra thought about it compared to ‘traditional’ games user research.

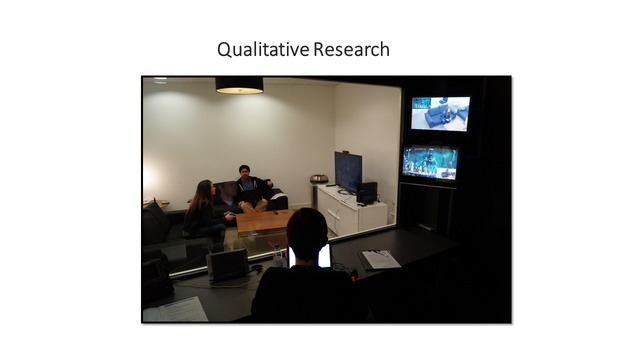

Normally the set-up of the room isn’t particularly important. This is a picture of our social room, a set up that most games user research labs also have.

It has a TV, some couches, and is just meant to represent a typical living room set-up. As long as you have the participant, and a TV they can play on, that’s good enough to get good quality usability feedback from.

However getting the room right is much more important for VR tests, because getting it wrong can cause plenty of issues with the game.

The first thing to think about is where to sit the player. Both Oculus and PSVR rely on line of sight between the camera and the headset – they use infra-red so that the game can track the player’s position, and allow them to move their head and body forward/back in the virtual environment, something not possible on stand-alone systems like GearVR.

Because of this, there’s an optimal place for the player to sit. If they are too far forward, or too far back, the system won’t be able to see them, and tracking will fail causing other issues in the game.

Be especially aware if the game will require movement – some of the demos that PlayStation have publicly shown require players to move between sitting and standing – so make sure that the player is sat somewhere the camera can see them both sitting and standing.

If the player is in a poor position, you’ll have plenty of potential usability issues – e.g. whether players recognise that the tracking is failing, and whether they know how to deal with it. However this is a system level feature, and so not the responsibility of the game you are testing – so development teams who have put the time and expense into organising the test will not be particularly happy if this occurs during their test, and obscures other potential usability issues in the game.

So, before starting, ensure the player is in the optimal position to play the game – which can be particularly an issue in multi-seat set-ups where many playtests are run simultaneously in the same room… but more of that soon.

Another common issue with usability labs is that they often have 1 way mirrors. Returning to the test we saw earlier ,we can see from the other angle that there is a one-way mirror in the room, which allows a note taker (and members of the development team) to observe the session. This is usually great – it gives a clear view of the context of the issue, and inviting the game team to come and see the session live allows the development team to come and engage with the session – paying more attention, and understanding the issues greater than watching later on a video.

However because many VR headsets use the IR sensors, the one way mirror can be a potential issue. It’ll cause a duplication of the IR sources for the camera, which can cause the quality of positional tracking to degrade, again introducing interference and reducing the quality of the experience, which can impact usability.

Luckily there’s an easy solution to this. Our lab manager discovered that on Amazon they sell blackout blinds, which are bits of plastic that stick, like cling film, to glass. This takes seconds to attach and can blackout the window preventing the reflection of the IR lights. The development team will once again have to rely on the camera feed, but the players experience is more authentic.

Another thing to be aware of is swivelling chairs. These are very common in an office environment, and so can be found in some playtest labs.

However they are much less common in the home environment, particularly with home consoles, so are unrepresentative.

The issue with swivel chairs is that they cause players to lose their orientation, and ‘forget’ which way is forward (or which way the camera is). This can cause usability issues, but again they are unrealistic because players would be on a sofa at home, where the forward direction is much clearer just from the feel of it.

They also have wheels on, which can cause them to move, and be a safety issue when working with players who cannot see!

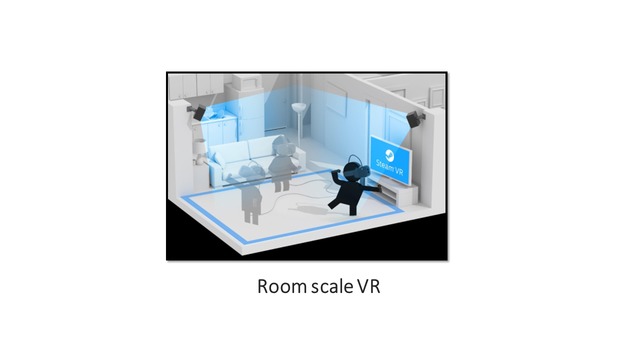

The last thing to mention is in regards to room scale VR. HTC Vive is built to allow players to walk around each experience physically. Oculus and PSVR have also both shown equivalent demos that allow players to physically move in a space.

For research on room scale VR – or anything that will encourage the players to move around – you want to keep the room free of obstacles (because they are walking around blindfolded in a room they are not familiar with).

Also remember not to move things – if you move a controller, or more importantly a chair, players will not be aware that it’s moved, which can cause safety issues.

So, to summarise this section on the room setup – extra care needs to be taken to ensure that the room setup isn’t going to cause ‘unfair’ usability issues that are out of scope for your current research.

Also remember to keep the user safe – don’t move things or let them walk into stuff!

The next thing I want to talk about is methodology – how the test needs to be adapted to run good quality user research sessions.

So, my favourite type of user research is 1:1 qualitative sessions. We usually have a moderator in the room with the participant, who can help ensure the game is running correctly and interview them at the end. We also have a note-taker behind the glass who can observe the usability issues, and write down players behaviours and what they say. This all works fine for VR tests.

One of my favourite parts of these sessions is probing players to understanding why players are acting in a specific way. For example, you can observe that the player walked straight past the next objective. But without probing, you cannot tell why – did they not see it? Did they want to collect something else first? Did they think they *needed* to collect something else first? The challenge is asking questions in the right way so that players are not lead to give the answer that they think you expect, so it’s like a puzzle, which is why I enjoy it. However, with VR there’s a problem with this…

…You can’t talk to the players as they play.

With the headset on, they can’t see you. These headsets also have 3D audio (so they can tell the direction of sounds), which requires headphones to work. Meaning they can’t hear you either.

This means that asking probing questions isn’t easy. There’s a couple of ways to address this.

- You can make sure your study design doesn’t rely on interruptions. Short play sessions to ask them questions after may be one way of doing this.

- You can watch the video back later with them, and ask them what their thoughts were. However this doubles the session length (which is bad in fast moving industries like game dev where teams start working on fixes immediately after seeing the issues). It also encourages players to attempt to justify their interactions by guessing, or trying to reason after the fact, which studies have shown humans are particularly bar at.

- One of the most encouraging things we’ve tried is to have the moderator talk into the player’s headphones. Instead of the audio signal going straight from the VR headset to the headphones, we’ve routed it through a mixing desk, which allows us to add other audio sources – such as a moderator microphone. This isn’t perfect as without visual cues players can be surprised by you talking to them, but with some priming can be a good work-around.

- It also stops you having to tap players on the shoulder to get their attention, which will break precense, and can be a big surprise!

Mult-seat playtests work fine for VR, with a few adaptions.

Because they are typically based on survey data and telemetry rather than observation, it means very little difference to moderation. However the room needs to be ready for VR – each player will need more space than usual as the games encourage movement. And again, any one way mirrors will need to be covered.

Also, because people are new to VR, they’ll need a lot more help getting setup. To help with this in multi-seat playtests, we often recruit extra temporary assistants to help with orientating players. We’ll talk more about that in a minute though.

So, as we’ve seen, some changes need to made to your study design to account for VR.

Making sure that you work around not being able to communicate with your participants is the biggest area to focus on. And ensuring that your multi-seat playtest area has enough room to run quantitative studies.

The next area I want to talk about is recruitment, and working with the participants for user research sessions.

The first thing to remember is that VR is a new medium, and most people have no experience with it.

This means that there’s a lot of things you’ll have to help them with, starting with how to get the headset on. It’s important to remember that people new to VR do not know what it should look like, and so will not be able to assess if it’s in properly/in focus etc. And because you can’t see what they are seeing, you can’t tell them. Because this is not the focus of your test, and will cause usability issues, it’s something that the moderator needs to deal with.

There are a couple of things you can do to handle this.

- First, prepare a script to help them get the headset on. Make sure that it includes instructions on how to fit the headset, a way of assessing whether it’s on properly, and steps to resolve if the picture isn’t good.

- A good way of assessing if the picture is in focus is finding a menu with sharp text, and then asking them to tell you whether the text appears sharp, or blurry/doubled. As a test, its simple enough that most people can understand whether they’re seeing the correct thing or not, and then whether you need to help them further with the headset.

(This is a bonus slide cut from the original presentation for time. Enjoy!)

Another thing to consider is recruitment. Because VR is a very new tech, this impacts recruitment.

If you recruit based on intent to buy VR, that will have an effect on what demographics you get. So, looking for casual players who intend to buy VR will be unrealistic and make recruitment very difficult to find legitimate users. Although, you and your development team should probably consider why you want these users, as they will not be your customers. There are certain cases when casual players may be relevant for VR testing, for example social/party games, but it’s worth a second thought.

The other thing to be aware of is if you’re recruiting based on people who currently own VR, that introduces a very heavy bias on who your participants are. As VR is a niche product, and up until recently only development versions of the hardware has been available, anyone who owns a VR headset, (and most people who have tried them) are a-typical – very tech savvy and unrepresentative of a typical consumer. If you’re developing for a device intended for a home audience, such as consoles or mobile, care should be taken to ensure that they are representative.

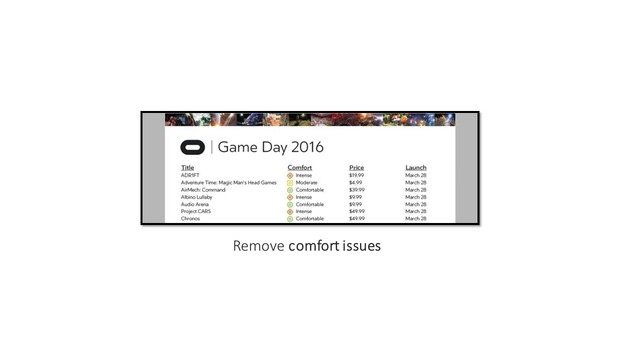

You should also be aware of is potential comfort issues.

On launch, oculus rated the comfort of each of their experiences – the likelihood that some people would feel a form of motion sickness, which implies that this can be an issue for some VR experiences.

When running usability tests, you don’t want to have to stop the session early due to people feeling ill. So, for usability tests you want to screen before hand for predisposition, through factors like “have you ever felt motion sickness when travelling” and “have you ever felt motion sickness when performing extreme activities”. This will help minimise comfort issues when playing, and ensure that you don’t miss out on getting usability feedback.

So, as we’ve seen with participants we’ll want to help people set up, recruit realistically, and minimise the potential for comfort issues.

The last topic I wanted to cover is how to deal with opinion data. First, of all, let’s start with the basics…

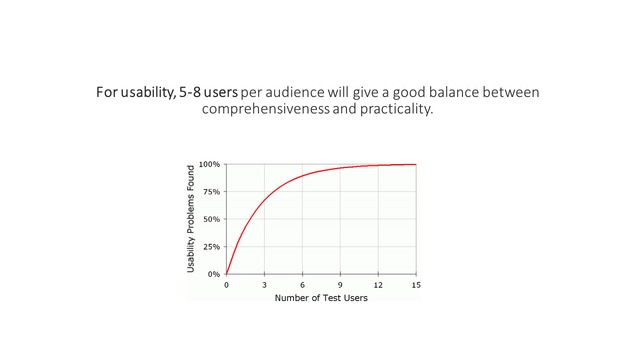

So, as we all know, Nielsen’s research has shown that 5-8 users per audience is a good number of users to be ensure you are discovering most participants, and is a good balance between making sure the results are comprehensive, but also that you are not running too many sessions and wasting the team’s money. This is great for usability findings.

But again, as we all know, this isn’t a good number for opinion data (whether people like things). Your test was designed to discover issues, but doesn’t give you any indication of how representative the data is – for usability or opinion data. If one person out of 5 had a usability issue, that could mean that 2% to 64% of the final audience may encounter it. And opinions are so much more diverse that any opinion data will not even begin to be representative.

Also the test is unfair for opinion data – players will have encountered usability issues, and in the past we’ve found that this will heavily influence their opinion – if you ask them what they like least about the game, they’ll probably start talking about usability issues they encountered.

Despite knowing all of that, there is always the temptation to ask opinion questions anyway in usability tests.

No matter how much you explain that the data isn’t particularly actionable, teams still usually want to hear it – so it’s very tempting to be naughty and include those questions.

This is usually a waste of time for VR games. People have no conception of what VR is like, and so there top opinion is almost always “its immersive”

“i imagined it would be a big TV, but it’s actually like being inside the game“

If you’re even naughtier and ask for ratings, players will rate VR experiences much higher than equivalent non-VR experiences.

However all off these opinions are opinions about the medium of VR, not the game itself, and so are not particularly relevant, or useful, to the game team.

There are a couple of things that might help get better quality opinion data from qualitative sessions.

The first thing to try would be a palate cleanser – let everyone try an initial VR experience before they play the real game, to get them over the “wow” factor, and bring them onto assessing the individual merits of this specific game.

However this wastes a lot of time – it’ll add at least 30 minutes to each session. And as we know, this opinion data is un-actionable anyhow, so it doesn’t make sense to extend the session to collect it.

You could also look at hiring expert users – people who have used VR before and are familiar before. However again, as we’ve seen earlier this will add a huge bias to the recruitment. That may be fine, depending on what you’re trying to learn from your test, but it’s important to be aware of for caveating any findings.

So, my recommendation – and best practise for all usability tests really – is to resist the temptation and ignore the opinion data. It’ll be unreliable and not worth compromising your study design to address.

If you’re after reliable opinion data, plan a different test for that.

So, here’s some of the things I hope I’ve covered about preparing to run tests in VR.

And that’s all! Thanks for reading 🙂

Leave a Reply